Soccer coaches in the present day are, for the most part, a lot different from the old days. Back then, the “brilliant” coaches were often master tacticians operating from a position of near-absolute control and authority.

Today, on the other hand, we see coaches much more concerned with building empathy and connection and working collaboratively with players to foster a positive team culture.

So what are the main styles of coaches today, and more importantly, how does that affect you as a player?

When you’re trying to improve your game, it’s important to think about the style of your team’s coach so you can determine how else you might need to supplement your development. This article will give you some points to consider. (And if you’re a coach yourself as well, this line of thinking can help you get the most out of your players.)

Crucial to this discussion are the age and level of competition for evaluating a coach’s style. A U-10 coach is obviously going to have very different goals from older players, and those teams have much different goals and missions. Try to determine (through observation and conversation): what is my coach’s ultimate goal for me and my team? Is it winning at all costs? Is it developing players to their fullest potential? Is it simply to have the players enjoy themselves and share a bond?

Another important question is how does your coach see his or her role relative to the team’s success? Tom Bates groups coaches into two types: transactional and transformational. Transactional coaches see players “as a ticket to validate their own personal needs to self-importance, status, and identity.” This results in practice sessions where the coach is constantly intervening in the activities and delivering mini-lectures. They also might take time to persuade others that they are the reason for a team win or a particular player improving. Transformational coaches, on the other hand, put player needs above their own. They have a “drive to create empathy, connection, and guidance” and put themselves “in their players’ shoes and ask what they need first.”

The National Institute for Child Centered Coaching makes a distinction between “traditional” coaches and “child-centered facilitators.” The traditional contingent “believes winning is the primary reason for playing sports; takes a hard line in discipline; uses an autocratic approach to coaching; (and) finds little value for parental involvement.” Child (or player) centered coaches, on the other hand, realize the value of making the game enjoyable, with varying attitudes towards the importance of winning and competition.

They also offer guidance and support and at the younger levels welcome parental involvement. They also don’t worry about players getting “spoiled” through praise. With respect to discipline, they have a “tendency toward leadership, not autocratic rule; problem solving, not ruling; motivating, not commanding.” They also won’t discipline players in front of the team to prove a point.

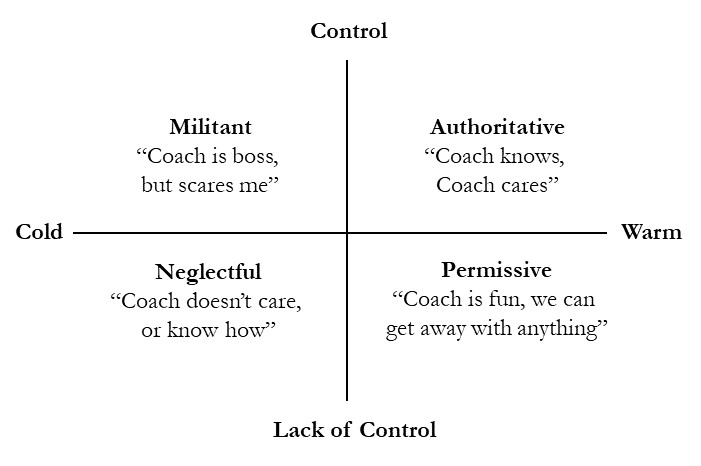

Tom Bates expands this into 4 distinct types of coaches along two different axes which were originally developed for evaluating teachers: control and warmth. Control refers to “maintain(ing) order and task progression within the (coaching) environment” while warmth is “the level of affection and positive energy” the coach elicits.

Source: https://www.bennionkearny.com/wp-content/uploads/2018/01/Control-Warmth-Matrix.jpg

Here, authoritative is the sweet spot between keeping order while still having empathy for the players. A permissive coach will be fun to play for, but the lack of control often means you will need to work on what’s best for you as a player outside of your structured team environment.

A neglectful coach, of course, will not give you enough individual attention to help you develop to your fullest potential, while a militant coach is unlikely to provide the empathy and understanding you may need. So how do you deal with a coach with these attributes?

In these cases, remember that you are in control of certain things, like your own effort and positive attitude, so focus on bringing that every time you play or practice. Try not to worry about the coach’s tirades, lack of attention, or whatever else that is out of control.

Committing yourself to individual (or small group) training is also a good way to ensure you are getting enough touches and working on what you need most if you aren’t getting that from your coach. This doesn’t have to be fancy or expensive private lessons, as you can find good exercises to work on from many sources including this website.

A good coach will also help you formulate individual goals, so if your does not help in this regard, set some yourself or in conjunction with a friend or parent. This could be anything from improving your finishing, maintaining your confidence after a mistake, or playing the winger position in a 4-3-3. Make a realistic assessment of your current level, what can be done to improve, and find ways to monitor your progress.